Finding the love hormone in a stressed-out world

A new art/science collaboration uses molecular structures as its creative medium.

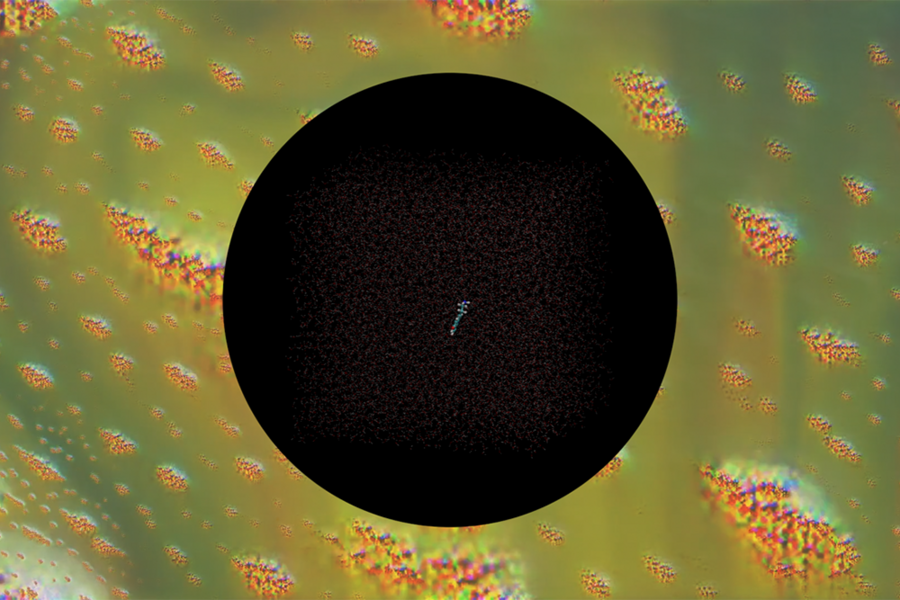

Caption:Video still from „Wet-on-Wet“, 2021, HD video, sound, 7’04’’

Credits: Jenna Sutela and Markus Buehler

In Jenna Sutela’s work, which ranges from computational poetry to experimental music to installations and performance, the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST) Visiting Artist enlists microbes and neural networks as co-creators.

“I want to explore this notion of expanded authorship through bringing in beyond-human life forms,” Sutela says. Inspired by science fiction, she employs both nature’s oldest technologies — the slime model Physarum polycephalum that has been compared to a computer — and the newest ones developed in research labs. Bacteria and artificial intelligence are among her many collaborators in creating artworks that challenge the deeply ingrained idea that humans exist apart from the teeming, vibrating world that contains us.

In April, Sutela participated in an Open Systems panel, moderated by Caroline Jones, professor of history theory and criticism, as part of this year’s CAST symposium. “Jenna Sutela operates in the fluid spaces of artistic knowing, bridging vastly separated topics from the ‚distributed intelligence‘ of slime mold to the ‚alien intelligence‘ flowing into a Victorian trance medium,” Jones notes, “When I proposed her for a visiting artist residency, I knew she would thrive in the edgy MIT research labs.”

As a visiting artist, Sutela was inspired by the sonifications of Jerry McAfee (1940) Professor of Engineering Markus Buehler, which are created by translating the vibrations of protein chains into audible sound. This is a field that she has been following attentively: different (still niche) scientific practices of observing life by listening instead of only looking.

As part of this research, Buehler had recently sonified the molecular structure of the coronavirus. “Not only can phenomena within the structure of materials — such as the motion or folding of molecules — be heard and open a new way to understand nature, but it also expands our palette of musical composition,” Buehler says. “When used reversibly, they yield a systematic approach to design new matter, such as new protein molecules that emerge from this process, complementing what evolution produces.”

“A lot of my work consists of using microscopes and telescopes to communicate things that are beyond our ability to experience firsthand,” Sutela says. She has given a voice, or a hum, to Bacillus subtilis bacteria that thrive both in our guts and in outer space. With the pandemic introducing a profound new global anxiety, Sutela wondered if the surge of chemicals that cause emotions such as love or bonding — what are referred to as “emotive molecules” in the project — could similarly be translated into perceptible form.

Seeing like a machine

Meanwhile, Buehler had spent the past decade listening to proteins and using them as “instruments” and a source for auditory compositions. He had only lately turned to making these molecular patterns comprehensible to another human sense: sight. By hooking an actuator up to a petri dish of water, he was able to see how molecular vibrations manifested as visible water waves. “But when I looked at all these different patterns from different proteins and mutations and I couldn’t really clearly distinguish them, I thought, ‘Maybe a machine learning algorithm might be able to do that, and help in the cross-domain translation,” he recalled.

The computer, with its artificial neural network, became a creative collaborator. “The computer has now understood the mechanisms of these vibrations and how they relate to different proteins, or molecules. Then I can actually take an image, and ask the algorithm, ‘What do you see in this picture?’” says Buehler. The computer then “draws” on the image, superimposing the patterns it detects on top of the picture to an almost psychedelic effect. In a photo taken of a recent trip to the seaside (like so many in quarantine, Buehler had found himself spending more time outdoors), he discovered the computer could pick out the invisible molecular patterns of the ocean and craggy rock.

An article by Anya Ventura for MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology

Read the full article here